Notizie per Categorie

Articoli Recenti

- [Launched] Generally Available: Instance Mix for Virtual Machine Scale Sets 22 Aprile 2025

- [Launched] Generally Available: Announcing the Next generation Azure Data Box Devices 22 Aprile 2025

- [Launched] Generally Available: Cross-Region Data Transfer Capability in Azure Data Box Devices 21 Aprile 2025

- [Launched] Generally Available: Azure Ultra Disk Storage is now available in Spain Central 21 Aprile 2025

- [Launched] Generally Available: Azure Firewall resource specific log tables get Azure Monitor Basic plan support 21 Aprile 2025

- Securing our future: April 2025 progress report on Microsoft’s Secure Future Initiative 21 Aprile 2025

- [Launched] Generally Available: ACLs (Access Control Lists) for Local Users in Azure Blob Storage SFTP 17 Aprile 2025

- [Launched] Generally Available: New major version of Durable Functions 17 Aprile 2025

- [Launched] Generally Available: Azure SQL Trigger for Azure Functions in Consumption plan 17 Aprile 2025

- [In preview] Public Preview: Rule-based routing in Azure Container Apps 17 Aprile 2025

Phishing campaign impersonates Booking .com, delivers a suite of credential-stealing malware

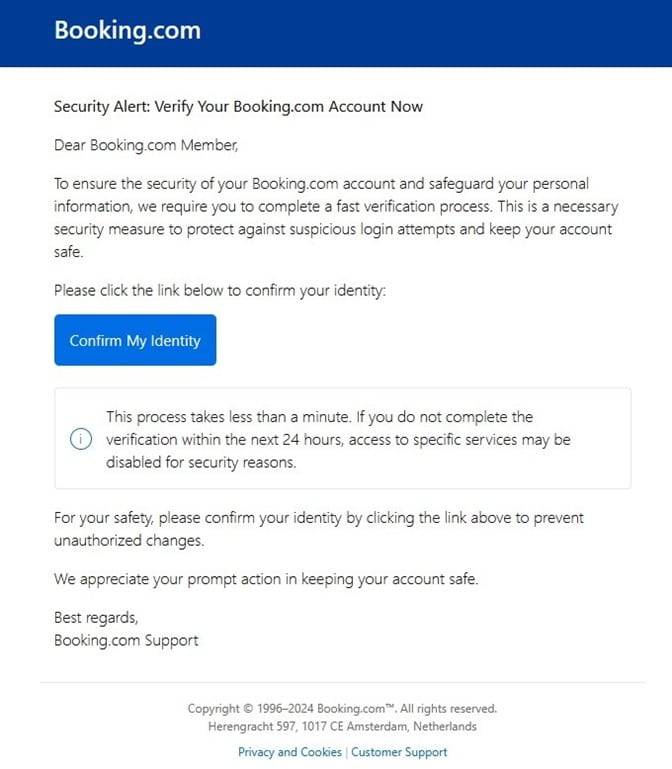

Starting in December 2024, leading up to some of the busiest travel days, Microsoft Threat Intelligence identified a phishing campaign that impersonates online travel agency Booking.com and targets organizations in the hospitality industry. The campaign uses a social engineering technique called ClickFix to deliver multiple credential-stealing malware in order to conduct financial fraud and theft. As of February 2025, this campaign is ongoing.

This phishing attack specifically targets individuals in hospitality organizations in North America, Oceania, South and Southeast Asia, and Northern, Southern, Eastern, and Western Europe, that are most likely to work with Booking.com, sending fake emails purporting to be coming from the agency.

In the ClickFix technique, a threat actor attempts to take advantage of human problem-solving tendencies by displaying fake error messages or prompts that instruct target users to fix issues by copying, pasting, and launching commands that eventually result in the download of malware. This need for user interaction could allow an attack to slip through conventional and automated security features. In the case of this phishing campaign, the user is prompted to use a keyboard shortcut to open a Windows Run window, then paste and launch a command that the phishing page adds to the clipboard.

Microsoft tracks this campaign as Storm-1865, a cluster of activity related to phishing campaigns leading to payment data theft and fraudulent charges. Organizations can reduce the impact of phishing attacks by educating users on recognizing such scams. This blog includes additional recommendations to help users and defenders defend against these threats.

Phishing campaign using the ClickFix social engineering technique

In this campaign, Storm-1865 identifies target organizations in the hospitality sector and targets individuals at those organizations likely to work with Booking.com. Storm-1865 then sends a malicious email impersonating Booking.com to the targeted individual. The content of the email varies greatly, referencing negative guest reviews, requests from prospective guests, online promotion opportunities, account verification, and more.

The email includes a link, or a PDF attachment containing one, claiming to take recipients to Booking.com. Clicking the link leads to a webpage that displays a fake CAPTCHA overlayed on a subtly visible background designed to mimic a legitimate Booking.com page. This webpage gives the illusion that Booking.com uses additional verification checks, which might give the targeted user a false sense of security and therefore increase their chances of getting compromised.

The fake CAPTCHA is where the webpage employs the ClickFix social engineering technique to download the malicious payload. This technique instructs the user to use a keyboard shortcut to open a Windows Run window, then paste and launch a command that the webpage adds to the clipboard:

The command downloads and launches malicious code through mshta.exe:

This campaign delivers multiple families of commodity malware, including XWorm, Lumma stealer, VenomRAT, AsyncRAT, Danabot, and NetSupport RAT. Depending on the specific payload, the specific code launched through mshta.exe varies. Some samples have downloaded PowerShell, JavaScript, and portable executable (PE) content.

All these payloads include capabilities to steal financial data and credentials for fraudulent use, which is a hallmark of Storm-1865 activity. In 2023, Storm-1865 targeted hotel guests using Booking.com with similar social engineering techniques and malware. In 2024, Storm-1865 targeted buyers using e-commerce platforms with phishing messages leading to fraudulent payment webpages. The addition of ClickFix to this threat actor’s tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) shows how Storm-1865 is evolving its attack chains to try to slip through conventional security measures against phishing and malware.

Attribution

The threat actor that Microsoft tracks as Storm-1865 encapsulates a cluster of activity conducting phishing campaigns, leading to payment data theft and fraudulent charges. These campaigns have been ongoing with increased volume since at least early 2023 and involve messages sent through vendor platforms, such as online travel agencies and e-commerce platforms, and email services, such as Gmail or iCloud Mail.

Recommendations

Users can follow the recommendations below to spot phishing activity. Organizations can reduce the impact of phishing attacks by educating users on recognizing these scams.

Check the sender’s email address to ensure it’s legitimate. Assess whether the sender is categorized as first-time, infrequent, or marked as “[External]” by your email provider. Hover over the address to ensure that the full address is legitimate. Keep in mind that legitimate organizations do not send unsolicited email messages or make unsolicited phone calls to request personal or financial information. Always navigate to those organizations directly to sign into your account.

Contact the service provider directly. If you receive a suspicious email or message, contact the service provider directly using official contact forms listed on the official website.

Be wary of urgent calls to action or threats. Remain cautious of email notifications that call to click, call, or open an attachment immediately. Phishing attacks and scams often create a false sense of urgency to trick targets into acting without first scrutinizing the message’s legitimacy.

Hover over links to observe the full URL. Sometimes, malicious links are embedded into an email to trick the recipient. Simply clicking the link could let a threat actor download malware onto your device. Before clicking a link, ensure the full URL is legitimate. For best practice, rather than following a link from an email, search for the company website directly in your browser and navigate from there.

Search for typos. Phishing emails often contain typos, including within the body of the email, indicating that the sender is not a legitimate, professional source, or within the email domain or URL, as mentioned previously. Companies rarely send out messages without proofreading content, so multiple spelling and grammar mistakes can signal a scam message. In addition, check for very subtle misspellings of legitimate domains, a technique known as typosquatting. For example, you might see micros0ft[.]com, where the second o has been replaced by 0, or rnicrosoft[.]com, where the m has been replaced by r and n.

Microsoft recommends the following mitigations to reduce the impact of this threat.

- Pilot and deploy phishing-resistant authentication methods for users.

- Enforce multi-factor authentication (MFA) on all accounts, remove users excluded from MFA, and strictly require MFA from all devices in all locations at all times.

- Configure Microsoft Defender for Office 365 to recheck links on click. Safe Links provides URL scanning and rewriting of inbound email messages in mail flow, and time-of-click verification of URLs and links in email messages, other Microsoft 365 applications such as Teams, and other locations such as SharePoint Online. Safe Links scanning occurs in addition to the regular anti-spam and anti-malware protection in inbound email messages in Microsoft Exchange Online Protection (EOP). Safe Links scanning can help protect your organization from malicious links used in phishing and other attacks.

- Encourage users to use Microsoft Edge and other web browsers that support Microsoft Defender SmartScreen, which identifies and blocks malicious websites, including phishing sites, scam sites, and sites that host malware.

- Turn on cloud-delivered protection in Microsoft Defender Antivirus or the equivalent for your antivirus product to cover rapidly evolving attack tools and techniques. Cloud-based machine learning protections block a majority of new and unknown variants.

- Enable network protection to prevent applications or users from accessing malicious domains and other malicious content on the internet.

- Enable investigation and remediation in full automated mode to allow Microsoft Defender for Endpoint to take immediate action on alerts to resolve breaches, significantly reducing alert volume.

- Enable Zero-hour auto purge (ZAP) in Office 365 to quarantine sent mail in response to newly acquired threat intelligence and retroactively neutralize malicious phishing, spam, or malware messages that have already been delivered to mailboxes.

Microsoft Defender XDR customers can turn on attack surface reduction rules to prevent common attack techniques:

- Block executable files from running unless they meet a prevalence, age, or trusted list criterion

- Block execution of potentially obfuscated scripts

- Block JavaScript or VBScript from launching downloaded executable content

- Block credential stealing from the Windows local security authority subsystem

Detection details

Microsoft Defender XDR customers can refer to the list of applicable detections below. Microsoft Defender XDR coordinates detection, prevention, investigation, and response across endpoints, identities, email, apps to provide integrated protection against attacks like the threat discussed in this blog.

Customers with provisioned access can also use Microsoft Security Copilot in Microsoft Defender to investigate and respond to incidents, hunt for threats, and protect their organization with relevant threat intelligence.

Microsoft Defender Antivirus

Microsoft Defender Antivirus detects threat components as the following malware:

- TrojanDownloader:Win32/XWorm

- Trojan:Win32/XWorm

- Trojan:Win64/Xworm

- Trojan:VBS/XWorm

- Trojan:MSIL/Xworm

- Backdoor:MSIL/XWorm

- TrojanDropper:Win32/LummaStealer

- Trojan:Win64/LummaStealer

- Trojan:Win32/LummaStealer

- Trojan:MSIL/LummaStealer

- Trojan:JS/LummaStealer

- Trojan:Win32/VenomRat

- Trojan:MSIL/VenomRAT

- TrojanDropper:MSIL/AsyncRAT

- TrojanDownloader:Win64/AsyncRAT

- TrojanDownloader:VBS/AsyncRAT

- TrojanDownloader:PowerShell/AsyncRAT

- TrojanDownloader:MSIL/AsyncRAT

- Trojan:Win64/AsyncRat

- Trojan:Win32/AsyncRat

- Trojan:VBS/AsyncRAT

- Trojan:PowerShell/AsyncRAT

- Trojan:MSIL/AsyncRAT

- Trojan:JS/AsyncRat

- Trojan:BAT/AsyncRat

- RemoteAccess:MSIL/AsyncRAT

- Backdoor:MSIL/AsyncRAT

- Trojan:Win32/Danabot

- Trojan:VBS/Danabot

- Trojan:Win64/Danabot

- TrojanSpy:Win32/Danabot

- TrojanSpy:Win64/Danabot

- TrojanDownloader:VBS/Danabot

- TrojanDownloader:Win32/Danabot

- TrojanDownloader:PowerShell/NetSupport

- TrojanDownloader:JS/NetSupport

- Trojan:VBS/NetSupportRat

- TrojanDownloader:JS/NetSupportRat

- Trojan:Win32/NetSupportRat

Microsoft Defender for Endpoint

The following alerts might indicate threat activity associated with this threat. These alerts, however, can be triggered by unrelated threat activity:

- Suspicious command in RunMRU registry

- Suspicious PowerShell command line

- Use of living-off-the-land binary to run malicious code

- Possible theft of passwords and other sensitive web browser information

- Suspicious DPAPI Activity

- Suspicious mshta process launched

- Suspicious phishing activity detected

Microsoft Defender for Office 365

Microsoft Defender for Office 365 detects malicious activity associated with this threat through the following alerts:

- This URL has known registrant pattern for malicious activity.

- This URL impersonates booking.com

- This PDF has generic phishing traits.

- This URL has generic phishing traits.

Microsoft Security Copilot

Security Copilot customers can use the standalone experience to create their own prompts or run the following pre-built promptbooks to automate incident response or investigation tasks related to this threat:

- Incident investigation

- Microsoft User analysis

- Threat actor profile

- Threat Intelligence 360 report based on MDTI article

- Vulnerability impact assessment

Note that some promptbooks require access to plugins for Microsoft products such as Microsoft Defender XDR or Microsoft Sentinel.

Threat intelligence reports

Microsoft customers can use the following reports in Microsoft products to get the most up-to-date information about the threat actor, malicious activity, and techniques discussed in this blog. These reports provide the intelligence, protection information, and recommended actions to prevent, mitigate, or respond to associated threats found in customer environments.

Microsoft Defender Threat Intelligence

- Storm-1865 phishing campaigns over vendor platforms lead to payment data theft and fraudulent charges

- Danabot

- NetSupport RAT

- AsyncRAT

- Lumma stealer

Microsoft Security Copilot customers can also use the Microsoft Security Copilot integration in Microsoft Defender Threat Intelligence, either in the Security Copilot standalone portal or in the embedded experience in the Microsoft Defender portal to get more information about this threat actor.

Hunting queries

Microsoft Defender XDR

Microsoft Defender XDR customers can run the following query to find related activity in their networks:

Network connections to known C2 infrastructure related to this activity

Look for network connections with known C2 infrastructure.

let c2Servers = dynamic(['92.255.57.155','147.45.44.131','176.113.115.170','31.177.110.99','185.7.214.54','176.113.115.225','87.121.221.124','185.149.146.164']);

DeviceNetworkEvents

| where RemoteIP has_any(c2Servers)

| project Timestamp, DeviceId, DeviceName, LocalIP, RemoteIP, InitiatingProcessFileName, InitiatingProcessCommandLine

Microsoft Sentinel

Microsoft Sentinel customers can use the TI Mapping analytics (a series of analytics all prefixed with ‘TI map’) to automatically match the malicious domain indicators mentioned in this blog post with data in their workspace. If the TI Map analytics are not currently deployed, customers can install the Threat Intelligence solution from the Microsoft Sentinel Content Hub to have the analytics rule deployed in their Sentinel workspace.

Below are the queries using Sentinel Advanced Security Information Model (ASIM) functions to hunt threats across both Microsoft first-party and third-party data sources. ASIM also supports deploying parsers to specific workspaces from GitHub, using an ARM template or manually.

Hunt normalized Network Session events using the ASIM unifying parser _Im_NetworkSession for IOCs:

let lookback = 30d;

let ioc_ip_addr = dynamic(['92.255.57.155','147.45.44.131','176.113.115.170','31.177.110.99','185.7.214.54','176.113.115.225','87.121.221.124','185.149.146.164']);

_Im_NetworkSession(starttime=todatetime(ago(lookback)), endtime=now())

| where DstIpAddr in (ioc_ip_addr) or DstDomain has_any (ioc_domains)

| summarize imNWS_mintime=min(TimeGenerated), imNWS_maxtime=max(TimeGenerated), EventCount=count() by SrcIpAddr, DstIpAddr, DstDomain, Dvc, EventProduct, EventVendor

Hunt normalized Web Session events using the ASIM unifying parser _Im_WebSession for IOCs:

let lookback = 30d;

let ioc_ip_addr = dynamic(['92.255.57.155','147.45.44.131','176.113.115.170','31.177.110.99','185.7.214.54','176.113.115.225','87.121.221.124','185.149.146.164']);

_Im_WebSession(starttime=todatetime(ago(lookback)), endtime=now())

| where DstIpAddr has_any (ioc_ip_addr)

| summarize imWS_mintime=min(TimeGenerated), imWS_maxtime=max(TimeGenerated), EventCount=count() by SrcIpAddr, DstIpAddr, Url, Dvc, EventProduct, EventVendor

Hunt normalized File events using the ASIM unifying parser imFileEvent for IOCs:

let ioc_sha_hashes =dynamic(["01ec22c3394eb1661255d2cc646db70a66934c979c2c2d03df10127595dc76a6"," f87600e4df299d51337d0751bcf9f07966282be0a43bfa3fd237bf50471a981e ","0c96efbde64693bde72f18e1f87d2e2572a334e222584a1948df82e7dcfe241d"]); imFileEvent

| where SrcFileSHA256 in (ioc_sha_hashes) or TargetFileSHA256 in (ioc_sha_hashes)

| extend AccountName = tostring(split(User, @'')[1]), AccountNTDomain = tostring(split(User, @'')[0])

| extend AlgorithmType = "SHA256"

Indicators of compromise

| Indicator | Type | Description |

| 92.255.57[.]155 | IP address | C2 server delivering XWorm |

| 147.45.44[.]131 | IP address | C2 server delivering Danabot |

| 176.113.115[.]170 | IP address | C2 server delivering LummaStealer |

| 31.177.110[.]99 | IP address | C2 server delivering Danabot |

| 185.7.214[.]54 | IP address | C2 server delivering XWorm |

| 176.113.115[.]225 | IP address | C2 server delivering LummaStealer |

| 87.121.221[.]124 | IP address | C2 server delivering Danabot |

| 185.149.146[.]164 | IP address | C2 server delivering AsyncRAT |

| 01ec22c3394eb1661255d2cc646db70a66934c979c2c2d03df10127595dc76a6 | File hash (SHA-256) | Danabot malware |

| f87600e4df299d51337d0751bcf9f07966282be0a43bfa3fd237bf50471a981e | File hash (SHA-256) | Danabot malware |

| 0c96efbde64693bde72f18e1f87d2e2572a334e222584a1948df82e7dcfe241d | File hash (SHA-256) | Danabot malware |

References

- Booking.com Customers Hit by Phishing Campaign Delivered Via Compromised Hotels Accounts (Perception Point)

- What is XWorm Malware? (AnyRun)

Learn more

For the latest security research from the Microsoft Threat Intelligence community, check out the Microsoft Threat Intelligence Blog: https://aka.ms/threatintelblog.

To get notified about new publications and to join discussions on social media, follow us on LinkedIn at https://www.linkedin.com/showcase/microsoft-threat-intelligence, and on X (formerly Twitter) at https://x.com/MsftSecIntel.

To hear stories and insights from the Microsoft Threat Intelligence community about the ever-evolving threat landscape, listen to the Microsoft Threat Intelligence podcast: https://thecyberwire.com/podcasts/microsoft-threat-intelligence.

The post Phishing campaign impersonates Booking .com, delivers a suite of credential-stealing malware appeared first on Microsoft Security Blog.

Source: Microsoft Security